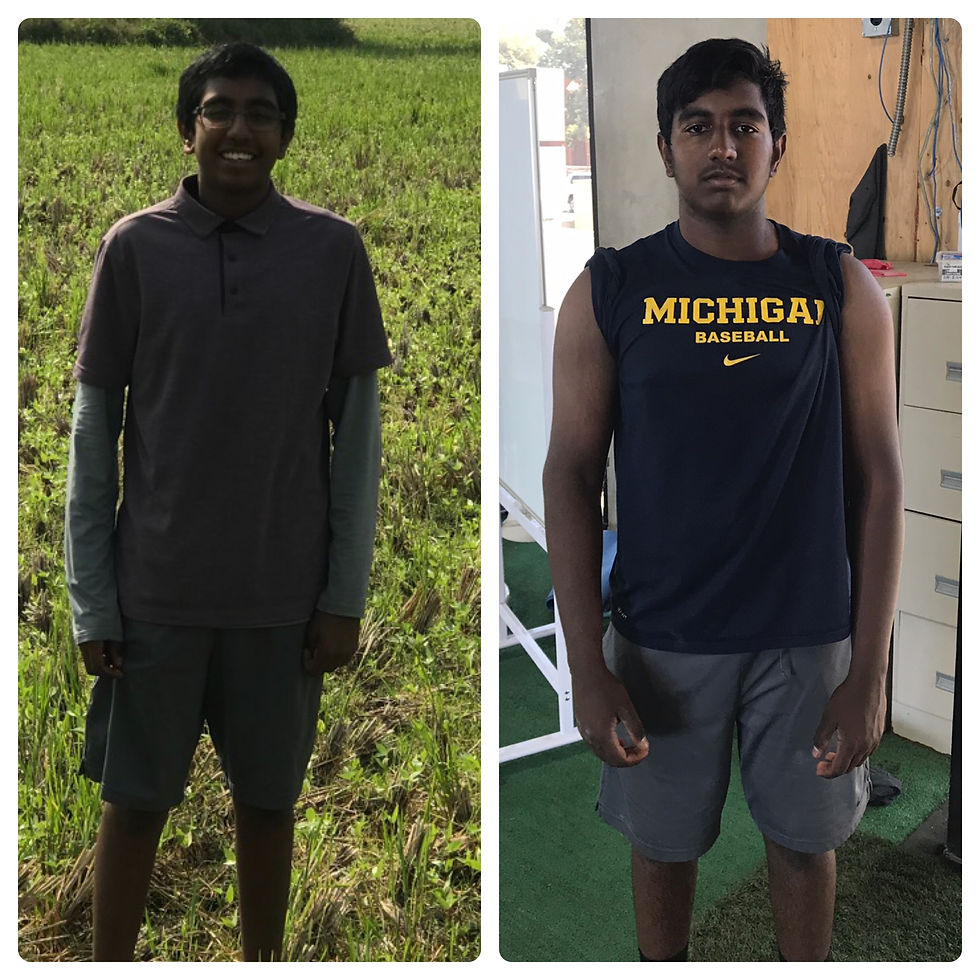

We had an interesting recruitment of one of our baseball pitchers this summer. He started with us his senior year of high school, and although he went 8-0 on the mound that senior year, the questionable competition his record was accomplished against, coupled with his underwhelming 83-85mph velocity, left him going to a D3 school. However, where most would get discouraged, he continued to train, and now 2 years later, sat 90-92mph off the mound at the gym on a Stalker2 early this summer. We contacted numerous D1 schools with the video, and many of them offered him a scholarship. However, what was interesting was some of the responses of schools that we discussed him with. The conversations generally went like this:

"He's throwing this hard why wasn't he D1 out of high school?"

"He's improved a lot in the last couple years"

"Is he a problem kid? I don't understand why he wasn't on top prospect lists a couple years ago. We can't find him"

"Yes, he wasn't that good then but he's added nearly 10mph since. Like you saw, he's good now"

"But why wasn't he throwing that hard out of high school?"

"He's much much stronger and bigger now"

The conversations would go in circles explaining that while he wasn't a "talent" kid out of high school, he'd worked himself into a high level pitcher. The confusion is that for the top college programs, they typically only work with gifted kids; everyone they recruit out of high school is extremely talented, and often deciding between signing in the MLB draft, or going to college. That there are kids out there who have patiently worked themselves over years from being mediocre into being great is a foreign concept. And who can blame them? In the baseball world, it's like spotting a giraffe in South Dakota. It never happens. Because whereas in other major sports athletes invest huge amounts of time and money towards improving their speed and power, much of baseball is still stuck in the 1960's. Many kids are unsure of whether to even lift weights at all, bumbling around doing physical therapy workouts that the average couch potato wouldn't find challenging. Uninformed or sometimes simply unmotivated, they fail to realize that if they'd work to grow their raw physical abilities, they also could become "talented" and compete right along with the gene code kids (those who played high school varsity as freshman, and often eased through the lower levels of the sport without having to really apply themselves). Failing to apply themselves, the untalented kids are left with flat fastballs and little to no speed or power, and are eliminated at each level that exceeds their talent. The myth that only those with special genetic qualities can succeed is perpetuated.

As we tell kids at the facility, if you're not a gene code athlete, you will be behind many of your peers, often for years. But you will never truly know if you were capable of catching up and succeeding, until you apply yourself to consistent, intelligent hard work over TIME. Then you will be able to say, like our pitcher at the start of this article, persistence pays.

Semper Fi

A. Fenske

Comments